Melting The Image That Unfreezes Your Gaze

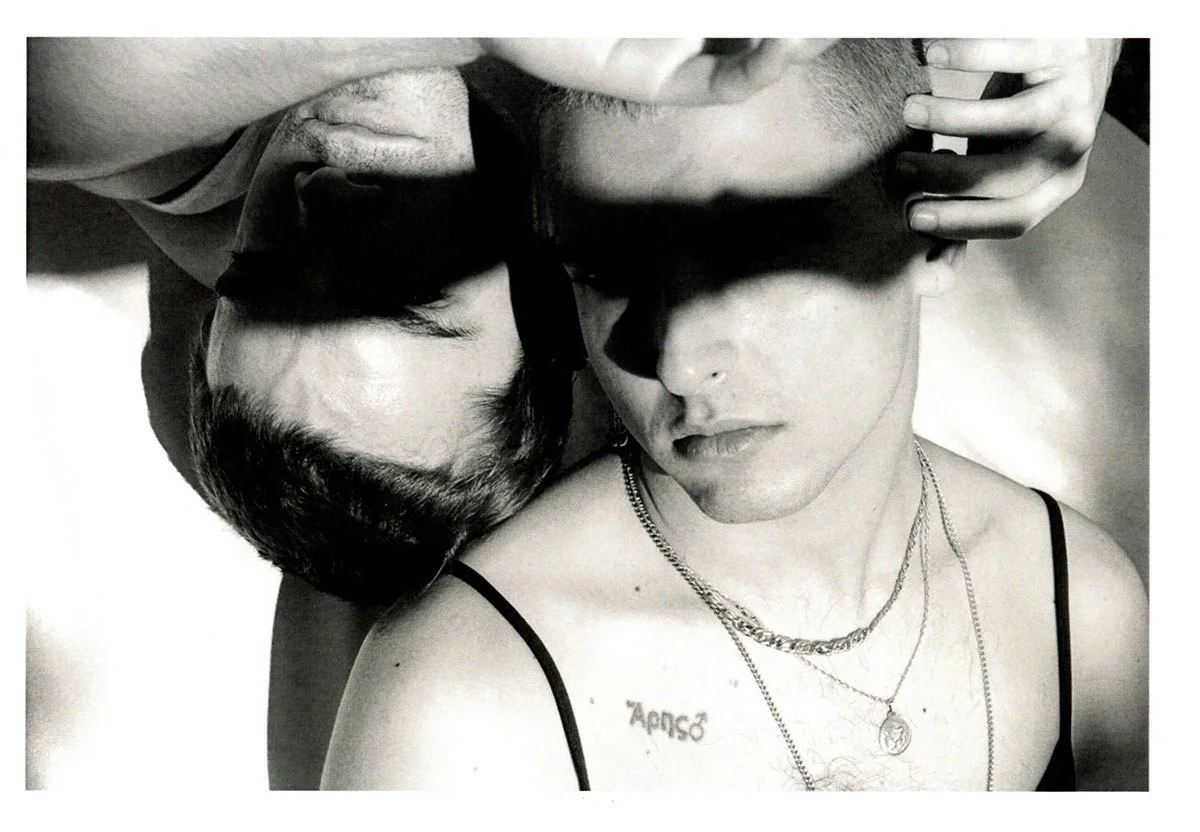

The editorial offers to discuss the subject of normativity and stop to think about the topic of the male gaze in art and photography. Marcos del Rio and Aimar Odriozola, contemporary dancers, become an essential part of constructing and allowing the fluid form in the story to emerge. The body movements, the extended black fabric, the improvisations on set come to symbolize the necessity for fluidity.

Unmelting the gaze is a fundamental appeal that comes in a physical form of unmelting the frozen images supported by a deeper-rooted idea of diversity and acceptance. Maite’s intention is to allow “the opening of a path that allows everyone to be free from the constraints of binary gender.”

Melting the Image That Unfreezes your Gaze is a story shot in Madrid by a London-based Spanish photographer Maite de Orbe. The photoshoot takes a modern approach of questioning the known medium, challenging the norms to create a new form of representation of the subjects. The photographs were frozen in order to, later on, be placed below the heat of Madrid's sun to melt, get dried, and scanned in the final steps of the process.

‘Images have the power to make something trendy, and this is fundamental in what we understand as socially acceptable or not. When we consume visual narratives, these subtly enter our minds and collaborate with normalization of what we are seeing in the image.’

What is Melting The Image That Unfreezes Your Gaze about?

Maite: This series aims to challenge a normative gaze as well as to reflect on the power of photography to make things fashionable; images have the power to make something trendy, and this is fundamental in what we understand as socially acceptable or not. When we consume visual narratives, these subtly enter our minds and collaborate with normalization of what we are seeing in the image.

What is the main idea that was important for you to convey through photographs?

Maite: So far in history, we’ve been accustomed to a male, dominant gaze, and this is the gaze that I have aimed to unfreeze. Also, photography has had a trajectory in the past of being a source of information that is reliable, and I wanted to demystify this; every picture is subjective and, therefore, reinforces the idea that the photographer had at the time of taking it.

By melting the image and unfreezing the gaze, my intention is to profane the medium and propose new ways of looking and telling stories that escape the oppression inherent to the male gaze. With this symbolism, I aim to make beautiful liquefaction of the gaze, to make it fashionable, and therefore, collaborate in its global acceptance.

‘The concept and creative process that I had in mind had a very experimental approach, but Marcos and Aimar agreed to it. They are both amazing contemporary dancers, and my practice is very much grounded on the human body.’

How was the process like working with Marcos and Aimar from the point of preparing for the shoot and the shooting day on set?

Maite: Working with Marcos is always amazing. I met him a few years ago and have already worked with him previously. Then I moved to London, and he started modeling for some great photographers in Spain, so it was very exciting to meet back again and work together. There is a lot of confidence between us, we shared ideas aesthetically and conceptually and trusted each other’s talents for the moment of the shoot.

‘I do not intend for everyone to suddenly change their gender pronoun, but rather collaborate in the opening of a path that allows everyone to be free from the constraints of binary gender.’

The concept and creative process that I had in mind had a very experimental approach, but Marcos and Aimar agreed to it. They are both amazing contemporary dancers, and my practice is very much grounded on the human body, so that was another common point that made everything very easy. I like to understand the body as a biological machine rather than a sexualized object, and they understand the body as something that enables them to work. On the day we shot next to Marcos’ place in Madrid, and this was very exciting for me as it was a place that brought him a lot of memories. We flowed and improvised around very easily, taking breaks to talk, smoke, and laugh. As the concept of this series is based on experiences of an oppressive system, the process of image-making had to be warm and listening. It was an equal collaboration between all of us.

Speaking about the gaze, the gaze of the other which can accept or deny the person’s existence, viewpoint, or personality, what were some of the concepts that drove you towards the creation of the story from the studies you refer to (Judith Butler, Paul B. Preciado, and John Berger)?

Maite: My interest in gaze is on how it sustains oppressive ideologies that build prejudice around those who are different from what is considered ‘normative.’ It's from photography and representation that I want to challenge this.

John Berger wrote a lot about this representation and, more specifically, the male gaze and how we learn to see each other from this particular gaze. So even though I am not a man, I look at the world from a male perspective. I take this as a way in which we have learned to oppress ourselves. From Judith Butler and Paul B. Preciado, I have understood gender theory and how binary gender can sustain this oppressiveness.

While Butler examines what she calls ‘gender performativity,’ repetitive actions that are associated with being male or female; Preciado proposes ways to radicalize it. With this, I do not intend for everyone to suddenly change their gender pronoun, but rather collaborate in the opening of a path that allows everyone to be free from the constraints of binary gender.

Could you describe the technique you used to take the images and post-producing the final result?

Maite: Although I normally work in film, for this occasion, I have decided to shoot digitally as this medium supported the idea of fluidity better than an analogue process. All the images were taken, edited, and printed to then be frozen in different containers. Then the ice was placed under the sun, and the process of melting was photographed too. This was fundamental for the piece as the changes in temperature had physical effects on the images, which you can appreciate in the worn-out ink and the rusty corners. As images are becoming more and more immaterial and digital, it's very important for me to give them a sense of materiality. Once the images were dry from the sun, they were scanned and curated to create this narrative.

What is the most memorable moment or episode from the shooting day or the preparation for it?

Marcos: The most memorable moment was a conversation in a bar before the shoot, having a space to share our views and terms about what we were gonna do so we could really work together. It also provided a friendly environment that made everything easier and reassured that everyone involved would be happy with the portrayal of their personal image and artistic views in the final result.

‘I could see from where I was standing that the picture Maite was taking was going to be great.’

Aimar: The most memorable moment from the shoot was when we took the picture of Marcos with the big black cloth behind him. The location was super cool, and it was a lot of fun playing with the wind and the fabric. I could see from where I was standing that the picture Maite was taking was going to be great.