Reconstructing Queer Intimacy

Jesse van der Berg is a photographer from the Netherlands who has recently graduated from the Master Institute of Visual Cultures. We introduce his graduation thesis, the research project Reconstructing Queer Intimacy, in which Jesse emphasizes the importance of presenting queerness from the queer gaze. The main goal is to drive towards crafting a new norm, educating on a different perspective.

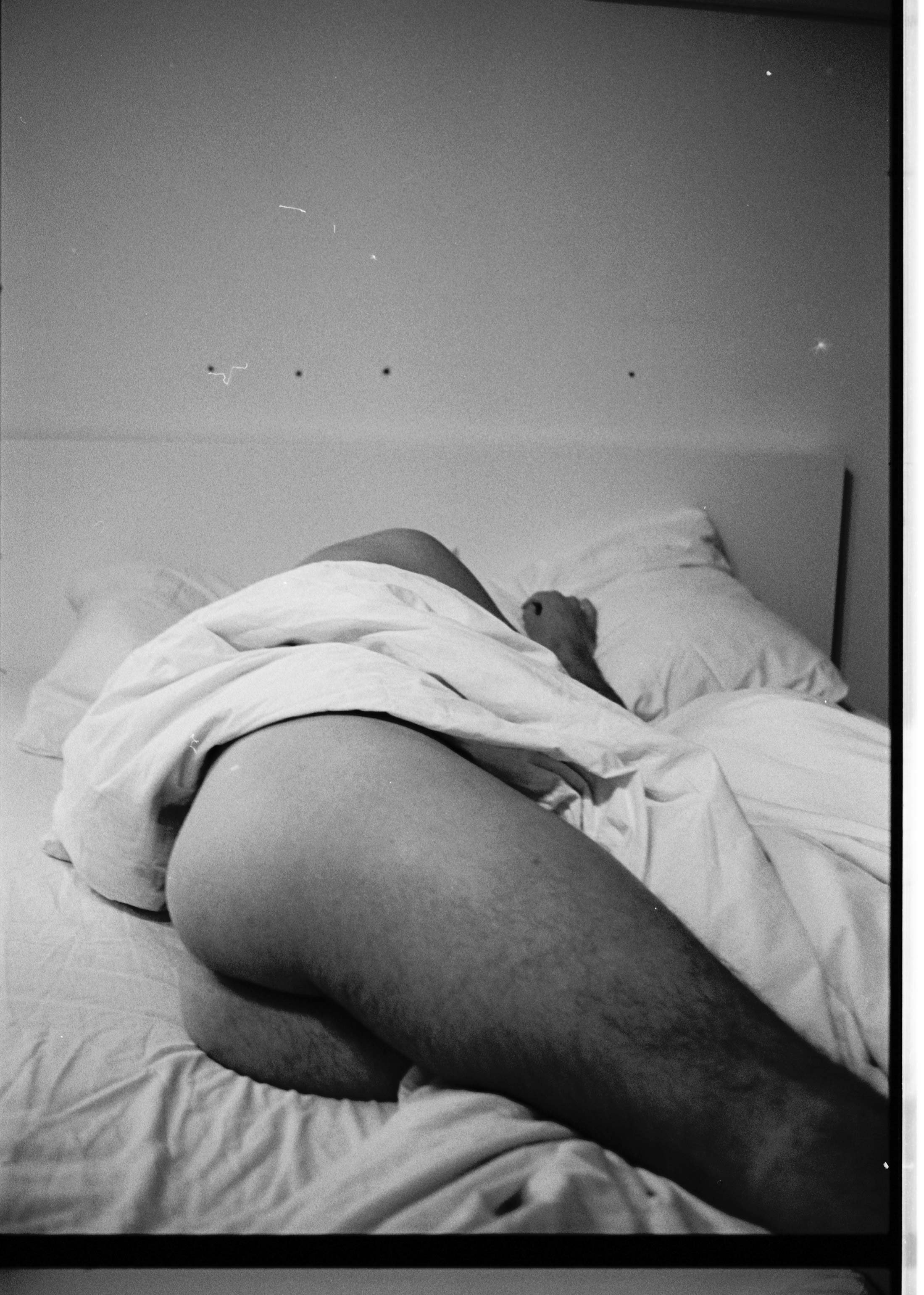

The outcome is a shift in the narrative; the shift opens new ways for communication and expression and enables empowerment of the subject and self-acceptance. Jesse’s approach is to investigate sexuality and the body through the means of analog photography. We see the exploration of intimacy embodied both in the process of connecting with the subject and the technical approach of shooting on film.

We discuss with Jesse his project with a spotlight on the personal perception of intimacy, on the importance of looking at the topic from the queer perspective, and the stereotypes that still affect society. As Jesse explains, “When queerness gets represented from the straight gaze, it’s often based on stereotypes and a lack of 'real' information and experiences from queer people themselves.” An additional topic of interest for Jesse is diversity among queer people and the aim to broaden the representation and include different types of body and gender identities. This process of exploration allows Jesse to learn from the people he photographs about himself and to share experiences in in-depth conversations.

Photography Jesse van den Berg Talents Bappie Kortam Erdem Gesmiroglu Laurens Zevenbergen Cheraldo Valpoort Andy Vandervoort Daan Versluis Bart Lieven Ingmar Harry

‘During the second year, my teacher Yin Aiwen told me that she had the feeling that I was searching for a kind of 'approval' from the non-queer people to be part of the conversation around intimacy. From that moment, I slowly realized that I don’t have to compare my view on intimacy or my work to the heteronormative way of talking about intimacy.’

Hi Jesse, you recently graduated from the Master Institute of Visual Cultures. We always have a memorable experience or a quote from one of the lecturers that has an impact looking forward. What was your meaningful experience during the studies?

Yes, I graduated in September 2020, a very weird time to graduate from an art school during COVID-19. There were multiple moments that had an impact during my study, but looking back on the past two years made me think of one specific moment. During the second year, my teacher Yin Aiwen told me that she had the feeling that I was searching for a kind of 'approval' from the non-queer people to be part of the conversation around intimacy. From that moment, I slowly realized that I don’t have to compare my view on intimacy or my work to the heteronormative way of talking about intimacy. From that moment, I felt more free in my view on this topic and also the way I look at my own work and others' work. I am here to tell the story of my models and me, and we don’t need approval. We are here, and that won't change. It did not necessarily change the process or visual output of my work but more the way I talk with people about my work. These conversations about queerness and intimacy are very important in my work.

‘What I see is that the straight gaze often depicts queerness with, what I call, a 'spectacle' effect. It feels that straight people expect something to be different, weird, or extreme when they talk about queerness and intimacy.’

You speak about the straight gaze, a topic which is often questioned by the misrepresented or underrepresented strata of society, which is also rapidly changing today, thanks to photographers and not only. How do you think the approach to the topic of queerness changes the discourse when presented from the queer gaze?

When queerness gets represented from the straight gaze, it’s often based on stereotypes and a lack of 'real' information and experiences from queer people themselves. What I see is that the straight gaze often depicts queerness with, what I call, a 'spectacle' effect. It feels that straight people expect something to be different, weird, or extreme when they talk about queerness and intimacy. When queer people are the ones in charge, they probably won’t necessarily focus on the part that makes them queer but more on the theme, and queerness is an inherent part of this. In my project, there is a focus on the topic of intimacy and queer bodies, but the parts that make us visibly queer are not necessarily there. Or well, I feel it’s always there, but it’s not the focus point.

‘Researching the camera as a present object in this intimate setting between the maker and the model was an essential part of my project. The first time that I’ve worked with a nude model was also the first time that I photographed with an analog camera.’

Intimacy can not only be researched and depicted through a photographic lens but also felt. How was the project conducted?

Researching the camera as a present object in this intimate setting between the maker and the model was an essential part of my project. The first time that I’ve worked with a nude model was also the first time that I photographed with an analog camera. I really liked the idea of not being able to see the immediate result, and it forced me to stay in the moment together with my model. I noticed that the interaction during this first analog shoot was indeed very different from the digital shoots that I did before. There was more focus on us, just existing in the space. This experience of a special and vulnerable moment together was one of the most important things during my research. And also, both the model and I felt completely comfortable during the process of shooting. Spending time with my model, developing the negatives, and scanning the negatives - all were critical in having an intimate moment with the model, but also with the visual output that I was creating.

‘The first time that I saw a video clip of mine, projected with a beamer on the wall, was the biggest revelation. I did this experiment in an old locker on the ground floor of my school. It created such a different way of experiencing the work because I was literally so close to the model, and I knew that the audience could experience this too.’

What was important for you during the process and the work with talents?

For me, it's critical that there’s diversity in the models I work with. I still see many queer projects that are mostly focused on white muscled cisgender queer men. When we talk about queerness, it’s necessary to represent queer people with different body types, cultural identities, gender identities, ages, and so on. Last week I had a shoot with a queer guy in a wheelchair. He texted me that he really liked my project and that he would love to see queer people with physical disabilities represented. So we had a shoot together, and now I am waiting on the negatives to arrive. It’s very nice to see that photography is able to connect people, broaden representations, and hopefully make people love each other and themselves more.

The moving image, through which you explore the body and allow a viewer to get closer on a more intimate level to the person presented, is a culmination of the project. It lets you cross the boundary of the static image with one step closer to entering the ‘real’ life scenes. What was your revelation during shooting the video fragments?

The biggest revelation from the moving images was not necessary within the process but more in experimenting with presentation forms. The first time that I saw a video clip of mine, projected with a beamer on the wall, was the biggest revelation. I did this experiment in an old locker on the ground floor of my school. It created such a different way of experiencing the work because I was literally so close to the model, and I knew that the audience could experience this too. I watched this one-minute video clip for quite a long time because I was amazed at how interesting the small movements and audio fragments were. It even made me emotional. It really felt like this was a new way of continuing this research on intimacy with such new potential.

‘We’ve come a long way, and now we’re here celebrating ourselves together. I think that every queer person has faced their struggles in the past, and seeing them and myself blossom up in a safe space is one of the biggest motives for making the work that I make.’

Living in The Netherlands, what do you think are the main changes in society regarding inclusion and diversity?

The urge for diversity and inclusion is getting bigger and bigger: from small platforms to the mainstream media channels. The Netherlands is overall a pretty good place to live, but we still have a lot of work to do. Two positive examples happened during the past weeks. In the Netherlands, we celebrate Sinterklaas every December. You could compare this to Santa. But Sinterklaas was always accompanied by Zwarte Piet. Black Pete is a character based on racist stereotypes. For a few years, more and more people are speaking up and demonstrating to get Black Pete removed. And this year, almost every city in the Netherlands got rid of it finally.

There also is a new platform called Omroep Zwart. That’s a new aspiring broadcaster in the Netherlands. They plan to be the first broadcast service on national TV where everybody will get representation: people with different cultural identities, LGBTQAI+ people, people with disabilities, and so on. They just got the 50K members needed to be able to join the Dutch broadcasting system, and that is great news. Those two concrete examples give me hope for a more inclusive future in the Netherlands, where everyone feels welcome and represented.

What is the most memorable moment or episode from one of the shooting days?

The most memorable moments of the shoots were the moments when my models and I had in-depth conversations about queerness, intimacy, sexuality, and we both felt comfortable, sharing a lot of personal experiences. This is very valuable for me. It makes me feel very proud of them, but also of myself. We’ve come a long way, and now we’re here celebrating ourselves together. I think that every queer person has faced their struggles in the past, and seeing them and myself blossom up in a safe space is one of the biggest motives for making the work that I make.