How to Climb a Mountain

How to Climb a Mountain is a durational performance choreographed and performed by César Brodermann and Guy Davidson. The eight-hour show was presented to live audiences in CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo and streamlined on Zoom as part of the out-of-office series of events held in Marc

Schimmel Multipurpose Gallery and led by Guy Bernard Reichmann together with Mona Benyamin and Esraa Abed. The project was supported by Batsheva Dance Company and Batsheva Dancers Create, with live music performed by Ariel Meriash and costumes designed by Ahinoam Chai.

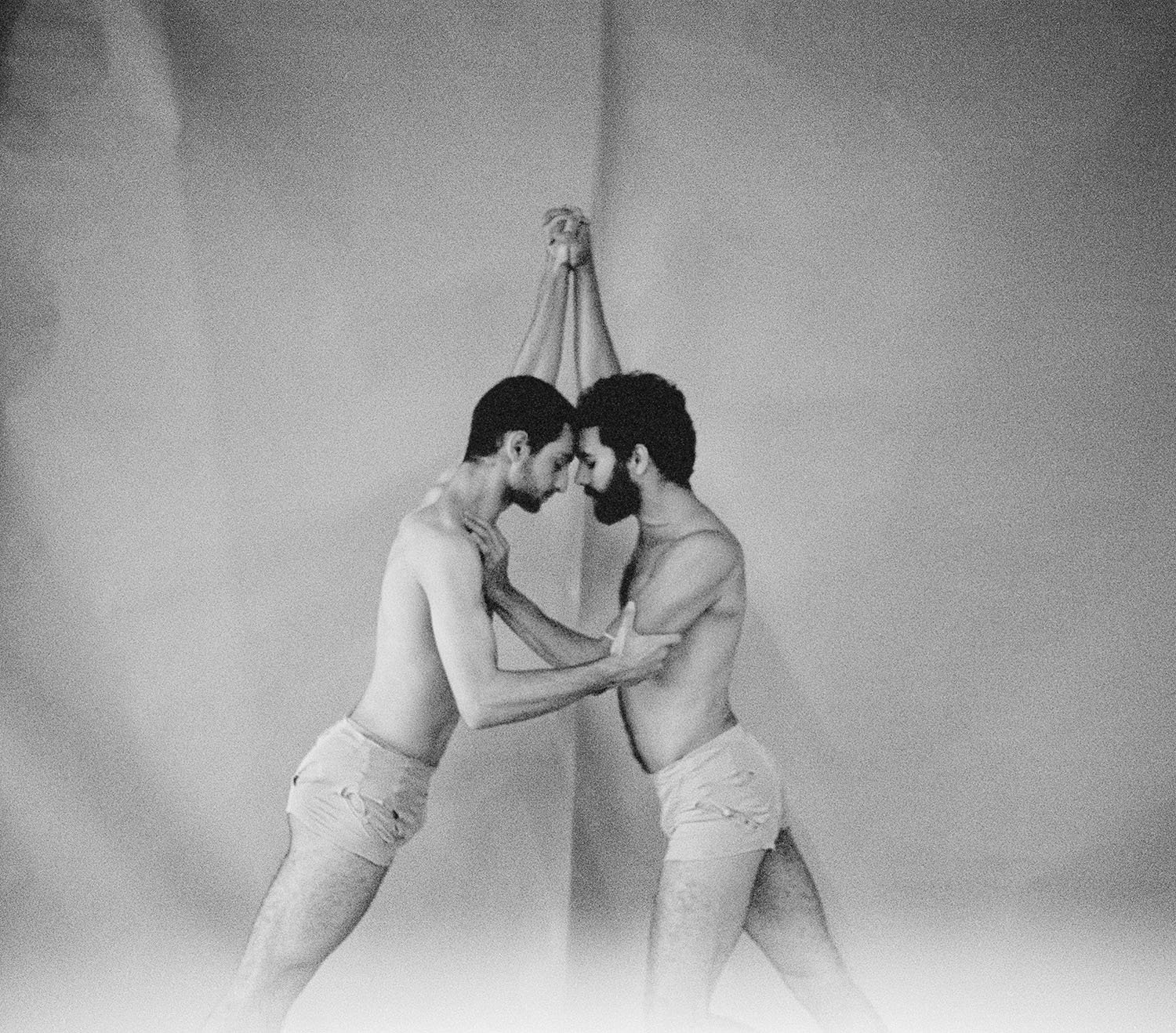

How to Climb a Mountain was inspired by the physical effort it takes to climb Mount Everest and the fastest climb that took 8 hours and 10 minutes, a record set in 2004 by Pemba Dorje Sherpa. The physical research of pushing one’s body to the limit was subtly intertwined with a metaphorical journey of hope and accomplishment. Guy explains, “I discovered what it feels like to be carried. I discovered what it feels like to be cared for. That drove me back to the moment and back to the goal.” The exploration is of strength that is derived from community, the sense of togetherness, the possibility to reach any goal, and overcome any challenge once united.

The theme of interconnectedness is a recurring one in César’s work that emerges through curiosity to explore the effect a person can have on a group and vice-versa. The idea of breaking the fourth wall and the decision to engage with the audience during the show sharing the experience of climbing the mountain comes as a climax in the curve of realization of interconnectedness.“ César shares, “In dance, we are used to performing for an hour and for the audience to sit and watch, but for me, it's important that the audience is active and constantly becomes part of the performance so that the audience/performer border is fully broken.” In this interview, we discuss with César and Guy in-depth the preparations for the durational performance and the experience during the show.

out-of-office

Duration 480 min

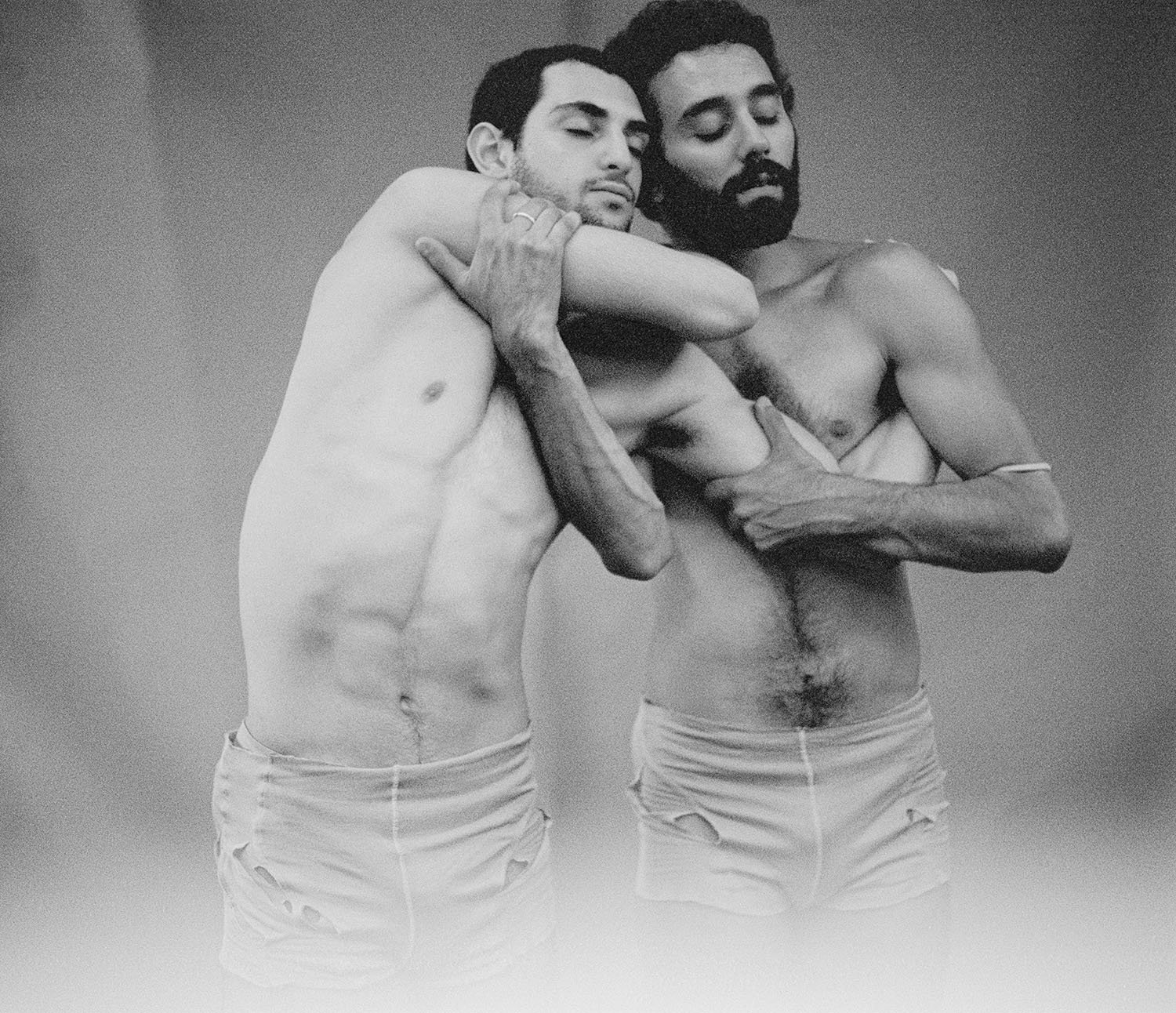

Performance by César Brodermann and Guy Davidson Photography by Jacobo Rios and César Brodermann Music by Ariel Meriash Costumes designed by Ahinoam Chai

Presented in CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo

Guy Bernard Reichmann Mona Benyamin Esraa Abed and Nicola Trezzi

Supported by Batsheva Dance Company and Batsheva Dancers Create

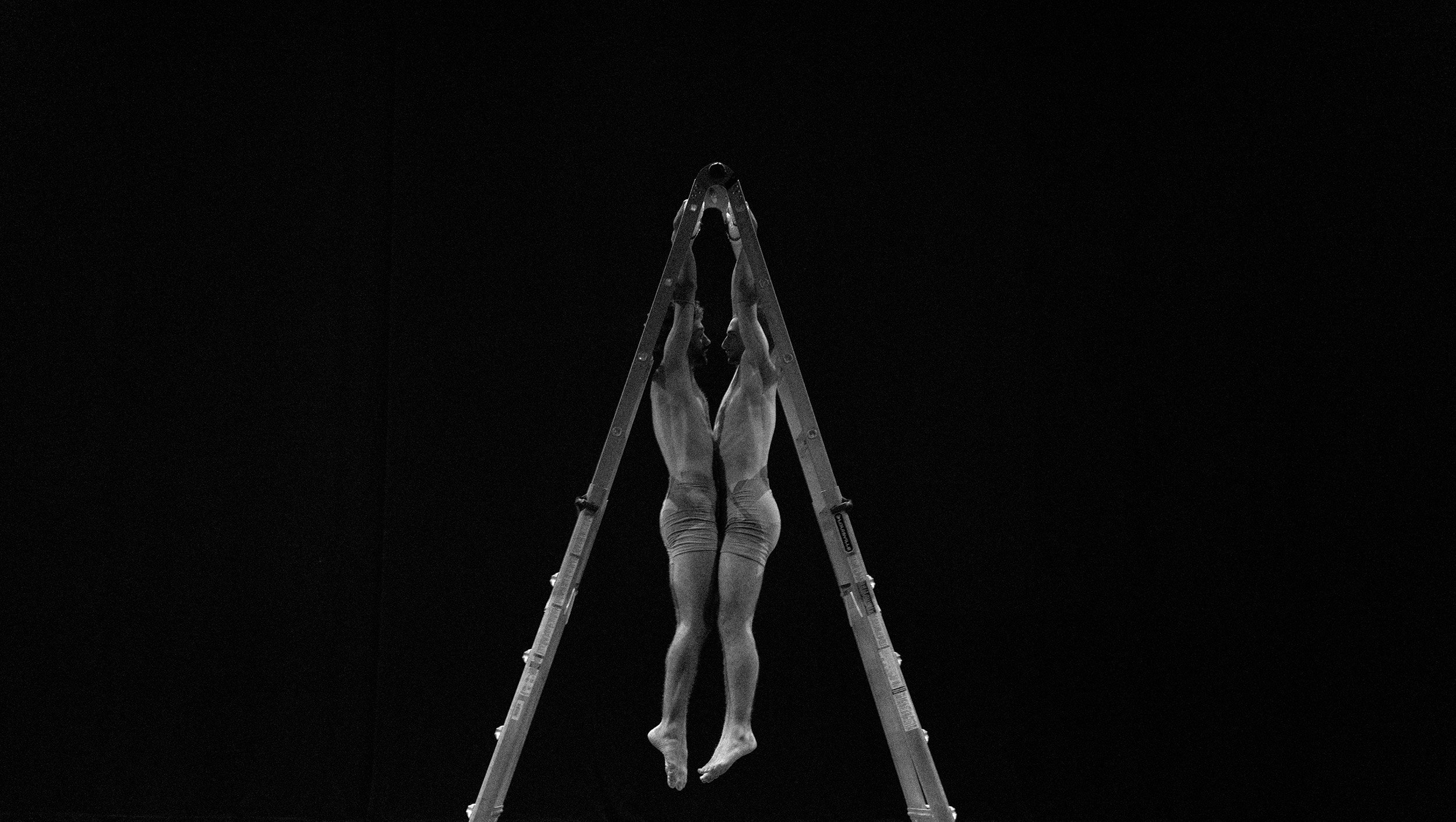

‘Inside the performance, we built a wall of ladders that I have been photographing since 2021. A ladder represents a mountain, this endless journey of always seeking more, of never arriving.’

— César Brodermann

Hi César and Guy, we’re so happy to present your latest work on WÜL! It’s actually your first durational performance you had as a duo. Tell about this experience of preparing for the show, the decision to film it and livestream to the wider audience, and the performance itself at CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo.

César:

WÜL! I’m so glad to be able to speak with you again. This was the most challenging show up to date, not only because of the duration of the show but also due to what needed to be done for us to go into the journey of 8 hours. I’ve learned with art creation that, most of the time, you have to put on 20 different hats to be able to make it happen: producing, creating, and getting all the materials. I feel lucky that I was able to create this show, hand in hand, with a lot of my closest friends and collaborators. One of the main sentences that inspire my work is “We can’t survive without each other,” and I really believe that the work is made this way. I love giving my all to the creative and production processes, and I wouldn’t be able to survive without the endless support that surrounded me to create the mountain to climb.

Guy and I have a truly special connection. In July 2022, I moved back to Mexico, which made us separate and continue with our own journeys — a really challenging moment. I have been traveling a lot, moving from place to place, and it always feels like a constant goodbye. Sometimes some people stay in your life, no matter what, and I believe me and Guy are like this, as artistic partners. We are devoted and committed to whatever we set ourselves to. While being far, we kept the research and rehearsal process going. We would meet almost every week to discuss and develop the movement language that would be used during the performance. Once I arrived in Israel in January, we reconnected all the missing pieces that we were building up, like a puzzle.

As a multidisciplinary artist, it is really important for me to combine more than one art form. Inside the performance, we built a wall of ladders that I have been photographing since 2021. A ladder represents a mountain, this endless journey of always seeking more, of never arriving. We also had three photographic and video installations in the lobby of CCA: Tel Aviv-Yafo. I feel this allowed the audience to be part of our journey on a deeper level, and the world was able to expand more with the installations around the space. I feel really thankful to Guy Bernard for offering us the ability to experience this type of performance. In dance, we are used to performing for an hour and for the audience to sit and watch, but for me, it's important that the audience is active and constantly becomes part of the performance so that the audience/performer border is fully broken.

The preparation for a durational show is very different from how to get ready for a dance performance of an hour. This is my first time performing durationally with a duet partner. I learned that you can only prepare that much. You need to trust each other and acknowledge that it will be challenging. What has always helped me is the determination to keep seeking and being in the present moment. The performance not only was about the effort of climbing a mountain but evolved into a meditation on how to take care of each other constantly.

Guy:

The preparation for this show was very different than for any other show I've ever done. Apart from the looming mountain-shaped shadow that I felt in rehearsals, the content was also different. Instead of choreographing a full piece in which everything is set with no random and unknown things happening, we prepared relatively short sequences of movement (some were brought from the short version of this show), and played with them during improvisation sessions. Most of the preparation for me was mental rather than physical. I was aware that it was going to be hard physically, but there was no way to prepare physically for an 8-hour show except actually doing the whole show in rehearsals (needless to say, that didn't happen). Preparing mentally proved tricky as well, but we always kept the image of climbing a very big mountain in our minds, and it was very helpful in the moment of truth. It helped me connect to the moment and my motivation to keep going. Moreover, reminding myself that we didn't need to fill up the entire duration of the show with movement and that there could be moments of quiet helped very much.

The show was physically easier than I expected but mentally harder. The first two hours of the show were some of the longest hours of my life. After they passed, I was shocked at the sight of the journey that was in front of us. I remember that I wasn't always able to fully connect to the moment, but as soon as I imagined where we were on the mountain and how much was left to climb, it sent me right back to this world and filled me with ideas. It was an image that was a deep well of inspiration for me: the taller the mountain got in my imagination, the deeper the well went.

In general, it was an exchange between physical power and mental power. As the show went on, I had less and less physical strength but more and more mental strength. There was also an interesting connection with the audience. Although I wish we could have expanded on that, it felt like we occasionally brought strangers into our journey, which reminded me of why we do what we do, and helped me to be grateful for the moment. The decision to film and broadcast the performance was very obvious to us. To share César's works with as many people as possible in real-time is an inseparable part of his work. He always tries to reach new and more people, whether it be across the same room or borders and oceans.

‘I’ve always been fascinated with time and pushing the limits of my mind and body, with the idea of how we can really keep going forever until we no longer can.’

— César Brodermann

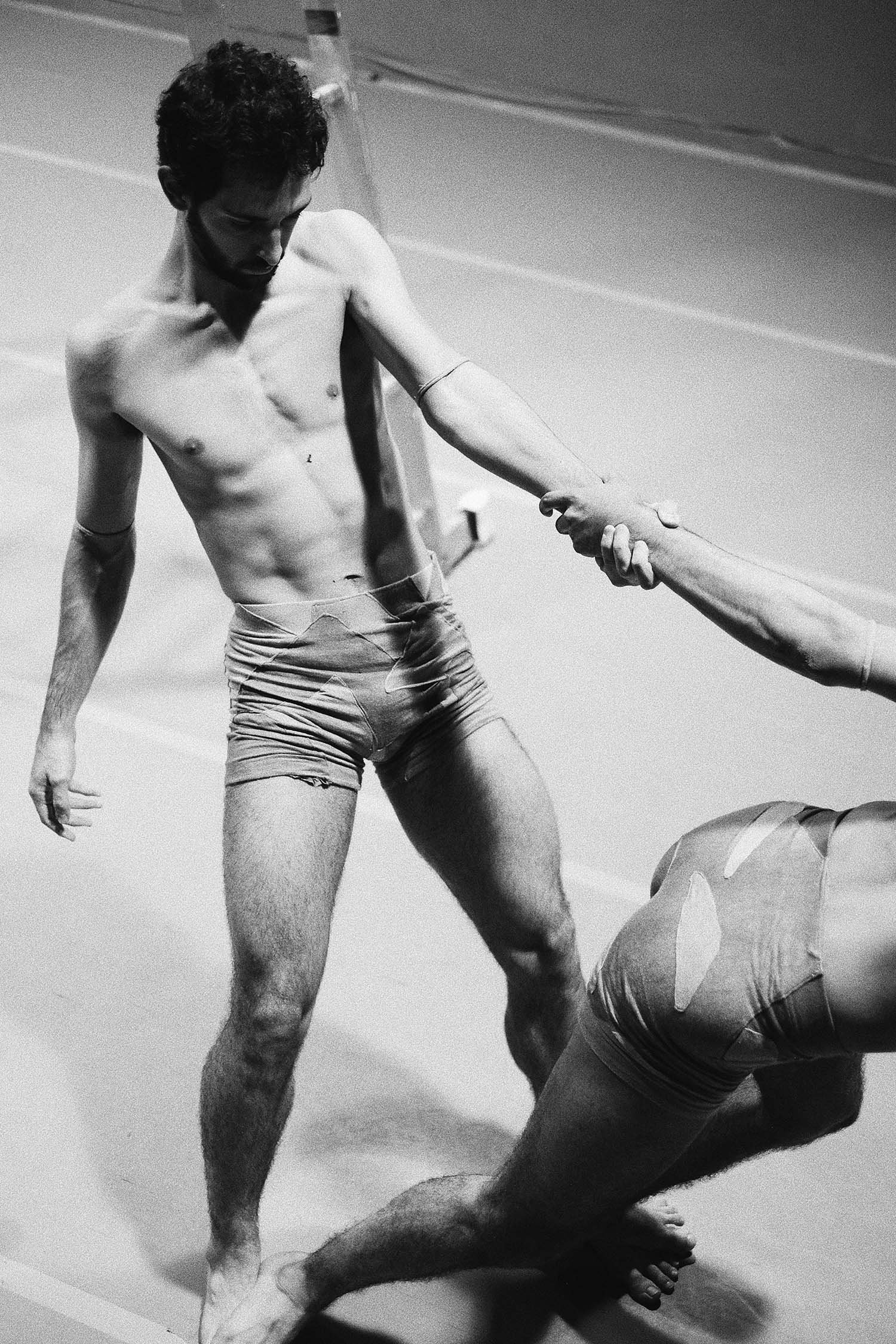

‘We were also trying to embody the physical effort it would take to climb Everest. Although we didn't know what kind of effort it required, we used each other, climbing and lifting each other to mimic the feeling of weight and the hardship of climbing a mountain.’

— Guy Davidson

How to Climb a Mountain started as a shorter performance that you decided to lengthen to the full eight-hour choreographed piece. As you explained, the inspiration came from researching the fastest mountain climb on Everest, which took 8 hours and 10 minutes, a record set in 2004 by Pemba Dorje Sherpa. What have you learned and incorporated from the research into the dance performed?

César:

I’ve always been fascinated with time and pushing the limits of my mind and body, with the idea of how we can really keep going forever until we no longer can. On the first day of rehearsals in 2021, I came to Guy and told him how beautiful it would be to climb a mountain together physically with dance and performance. I was wondering how it would be to perform for this duration with a partner. I feel really lucky to be working with Guy, someone who is willing to go 100% with me.

We wanted to honor the way and how long it takes to make the journey, which has stops, effort, landscapes, quiet moments, and challenging moments. We wanted to bring all of this to the research and become a mountain for someone to climb or a climber who is constantly reaching higher steps — this is where the ladder comes into the imagery. A ladder is shaped triangularly and has steps to climb, just like a mountain, so it was really important to me to incorporate this object into the performance. Even when we think we can't go one step higher, we find a way to do it with the support of each other. This is one of the main ideas that helped us survive this challenging journey. We have never climbed Mount Everest, but we talk about doing it one day to see the real challenge of it.

Guy:

In general, we took from this research the imagery and the embodiment of the physical effort of climbing a mountain. The imagery helped deal with the mental effort. Imagining and feeling where we are at climbing the mountain gave a big inspiration. Imagining what the journey requires (sleeping, resting, etc.) helped me understand that we don't always need to fill up the time with movement or activity happening, that we are here for a goal, and that we will do anything to reach it. We were also trying to embody the physical effort it would take to climb Everest. Although we didn't know what kind of effort it required, we used each other, climbing and lifting each other to mimic the feeling of weight and the hardship of climbing a mountain.

‘I discovered what it feels like to be carried. I discovered what it feels like to be cared for. That drove me back to the moment and back to the goal.’

— Guy Davidson

In your work, you always add a human aspect — the attempt to understand a deeper layer of interconnectedness, relationships, and the power of effect a person can have on another or a group of individuals — all done through the perspective of constant love and authentic care. Climbing a mountain or performing in a duo requires being in sync with your partner, their strengths and weaknesses, covering one another’s possible missteps, carrying the weight of each other, and eventually getting to the top of the mountain together. What was the toughest part during the performance, and how did you overcome it? What were the pieces planned as opposed to perhaps improvised segments?

César:

This performance became a meditation about taking care and mentally realizing how far we can go, not as individuals but with someone else together on this journey. The most challenging parts of the performance were when you were expecting or started measuring time. Once I felt lost in time, it became easier to be in the present moment and listen to Guy, the space, and the audience. There were a lot of moments of relief, hardships, and tears, especially moments that were not planned. We had interactions with the audience that we had never planned, but somehow they flowed, as well as choreographic parts or guided parts that we could access as the movement language of the piece.

The most challenging for me was once we reached seven hours. Having Guy with me constantly gave me the energy to keep going. Ariel was playing the guitar every step of the journey. Every two hours, I asked him to give us a musical queue so we could come back to our feet, to our ground, to this humanity, and restart from there. Exhaustion and pushing my limits are a constant in my work that allows me to connect to deeper parts of the self, learn how to keep going when you are empty, stay generous, compassionate, and empathetic, and try to be there for each other. I believe there's so much work to do, but I always want my performances to have hope because the world is too heavy. 'Endless hope' because maybe we will never arrive at that place, but we will keep pushing to find it. Together, step by step, climbing the ladder.

Guy:

This performance required us to be strong individually and be mindful of each other. It was a careful work of balancing the care for oneself and the other. I believe we always feel connected to each other no matter the hardships or distance, but this show tested the limits of that, especially towards the end when we were barely able to hold or lift each other or even able to move. I strongly remember the feeling of being very weak physically, but looking at Cesar and suddenly gaining power was almost magical. I feel like the connection with Cesar also helped to connect me to the moment. I feel like many times, I was so focused on him that I just stopped thinking. I just felt and sensed everything.

The hardest part for me was between the two-hour and the four-hour mark. At the beginning of that chunk of time, I realized how long two hours felt, and my mind wandered off to thinking about the fact that we had three times as much yet to go. Being there together really changed my perspective. I discovered what it feels like to be carried. I discovered what it feels like to be cared for. That drove me back to the moment and back to the goal. Clinging on to pre-prepared parts was also helpful. We read each other very well in the moment of truth, so we could seamlessly slide into unison or a built sequence, and it felt like these were anchors that we could cling to in this ocean of uncertainty.

‘I want people to arrive at our journeys and become a part of them. There is always audience interaction in some aspects of my performances. For me, it becomes a necessity. We can't finish the work without the audience.’

— César Brodermann

Throughout the performance, you engaged several times with the audience, including the last scene in which you and Guy pair people together to hold hands above their heads, closing the show by climbing the stairs. The engagement with people is metaphorical to the endeavor of climbing the mountain that emphasizes it can only be or better be done together. What is your experience of bringing people from the audience to the ‘stage,’ and why is it important to you?

César:

One of the most important factors in my art creation is how to break borders constantly. The border between the performer and the audience is a clear one in dance that I constantly seek to dissipate. I want people to arrive at our journeys and become a part of them. There is always audience interaction in some aspects of my performances. For me, it becomes a necessity. We can't finish the work without the audience. In a way, it's always about hard work and how we can support each other to keep going. We wanted to make people our mountains at the end, our landscapes. We wanted to become a ladder for others to climb and then for other people to become ladders for yet others to climb — an endless exercise of building something in the community.

Guy:

Sharing the stage with people that are not performers is a recurring theme in Cesar's work. It is about saying that dancers and the audience watching are not so different from each other, bringing in that human aspect that you talked about earlier, basically saying that this journey is universal no matter your background. It is an engaging feature of Cesar's work since it completely changes the power/control balance of the space. It's no longer an audience that came to see the show and performers that are the subject of attention. It's about people taking part in a journey together. In this specific show, the audience is shaped in the form of a landscape of mountains. It's symbolic in many ways, and creating it meant for me that many times the mountains that we face in our lives are people or are created by people, and that gives me hope because people (unlike an actual mountain) can care and support you on your journey.

César, going back from Tel Aviv to Mexico City, what are your plans for the near couple of months? What projects are you planning?

César:

I want to focus on my art creation, not necessarily dance, but performance, movement, photography, and film. I love combining different mediums to arrive at new places and journeys. Currently, I have four performers in Israel and seven performers in Mexico. My next dream is to be able to combine both casts for a new creation where we break borders and boundaries and learn from each other's cultures. There is so much to learn, and that always keeps me going and excites me. I do believe that art creation is something I will do for the rest of my life, and that is happening every second. I love the places we can reach when we commit, and I've been lucky to find special people on the way who commit just as much as I do.