I’m The Narrator Of The Story

For Mary Frey, the path to the sphere of photography seemed like the most natural one: starting from making images of her sisters as a kid with a “plastic, aqua blue brownie camera” followed by a realization during her college years that this is a profession she will pursue. As Mary explains, “ I came across the book, The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson, and knew immediately that is what I wanted to do.”

Her career at the Hartford Art School provides an additional distinct layer to her practice as a photographer, which enabled her to inquire into what stands behind a photograph, how does a photographer’s perspective add to the meaning of an image, to what extent an image holds truth. “I would argue that a photograph holds its own truth - or fiction - and therein lies its strength. [...] Thirty years ago, this idea may have been provocative, or at least conceptually thought-provoking.”

In this in-depth interview, we speak with Mary Frey about her childhood years, her projects Domestic Rituals 1979-83, Real Life Dramas 1984-87, series Body/Parts 1989-91, and Unsighted 1992-93. We talk about her book Reading Raymond Carver and her fascination with the author. We discuss the perception of the genre of documentary photography and staged images. Mary speaks about her recent comeback to shoot with a large-format view camera and the connection it allows with the subject. We close with her plans for this year and the new category Family, Friends & Strangers.

Mary Frey is a photographer from the US, currently living in Massachusetts. Mary earned her MFA degree from Yale University, later on accepting a full-time teaching position at the Hartford Art School, where she taught students for 35 years while practicing photography. Her work won numerous awards and was presented in various solo and group exhibitions throughout the US for over 30 years. Her first photographic book, Reading Raymond Carver, was published in 2017 by Peperoni Books. and was on the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation’s shortlist for First Photo Book for that year. Her second book, Real Life Dramas, was published in 2018. Currently, Mary Frey is working on her third book planned to see the light by the end of this year, “I’m currently working on the third book of photographs, which will include work spanning 40 years, acting as a bookend to complete this trilogy.”

‘I remember I had a plastic, aqua blue brownie camera as a child. I also recall that I would pose my sisters while they were playing and take pictures. Perhaps that was a precursor of things to come.’

I Am

Where did you grow up, and what is the first memory you have as a child?

I grew up in Yonkers, NY, a city that borders the Bronx, a borough of NYC. As a youngster, I had access to amazing museums, theater, and music venues, which definitely contributed to my lifelong interest in the arts and my subsequent career as a photographer.

I am the oldest of 6 children, and there were many snapshots taken of me and my siblings while growing up. So it’s hard for me to separate my first memory as a child from the experiences that were documented in our family albums. "Did I really remember that event - or believe I did - because I have the snapshot to prove it?” This idea surfaced later on when I was a young photographer and propelled me to work on one of my first photo projects, Domestic Rituals, from 1979-1983.

How did photography come into your life?

I remember I had a plastic, aqua blue brownie camera as a child. I also recall that I would pose my sisters while they were playing and take pictures. Perhaps that was a precursor of things to come. Nonetheless, I always had a facility for drawing and painting and studied visual art in both high school and college. It was during my sophomore year in college that I came across the book, The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson, and knew immediately that is what I wanted to do - make photographs. Some people are attracted to the medium because they love the process of photographing the world, others love the magic of working in the darkroom, I just loved photographs and how they held their own fiction, something that Cartier-Bresson’s work did very well.

Subsequently, I had many different jobs in the photography field. I sold cameras, worked in a darkroom, assisted in a commercial photo studio, researched and created archives for a hospital, spent a year documenting the activities on a college campus for their publications, taught in a community arts center, and picked up a variety of freelance jobs along the way. Throughout all those years, I always maintained my own artistic practice and participated in exhibitions when able. Nine years after college, I returned to study for my MFA in Photography at Yale, and after that accepted a full-time teaching position at the Hartford Art School, where I stayed for 35 years.

‘With my first major project, Domestic Rituals 1979-83, I began by playing with a large-format view camera and discovering how it worked. It was slow and unwieldy, and my subjects had to hold their pose to avoid movement.’

The Subject

Let’s speak about the subject the photographer decides to emphasize, to stop a moment and share with the viewer. What is your approach to choosing the subject and researching it?

The majority of my work stems from my own experience in the world and how to make shape of it through photography. With my first major project, Domestic Rituals 1979-83, I began by playing with a large-format view camera and discovering how it worked. It was slow and unwieldy, and my subjects had to hold their pose to avoid movement. I found that flashbulbs offered a type of light that was soft and enveloping, and combined with the large negative (4x5), rendered a hyperreal description of the surfaces of things. Conceptually, I was fascinated with the snapshot as both a vessel for and shaper of memory, and I tended to gravitate toward people for subject matter. As my aesthetic was coming together, I started to search for a 'project' to work on. While visiting my family for the Thanksgiving holiday, I set my camera up in the kitchen and waited. As my mother took a pie from the oven and raised it up for display, and it appeared to replace her smile - I had my “aha” moment. For the next five years, I sought out the most banal, everyday situations I could find and set my subjects up to appear as if they were truly engaged in their activities. I soon developed a 'cast of characters' willing to pose for me and allow me to invade their private lives. These images had a quasi-documentary look about them. They felt like tableaux-vivants of middle-class life, reminiscent of B&W film stills.

How did the themes of interest change throughout your practice?

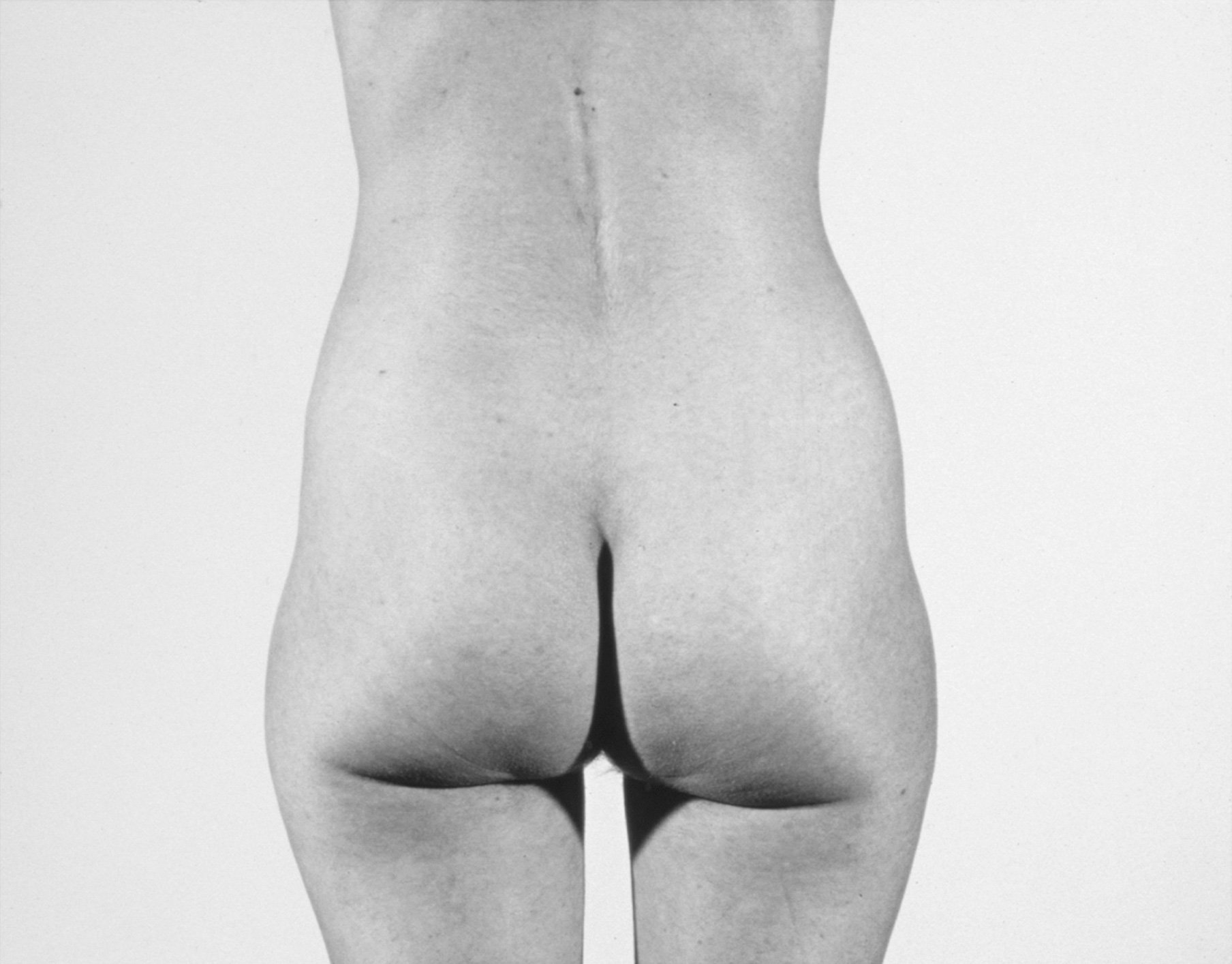

My series Body/Parts 1989-91 was made in direct response to a personal difficulty I was experiencing at the time. However, I chose to frame the work within the greater context of being a woman and confronting issues around gender and identity. The larger body images appear cold and clinical, suggestive of laboratory specimen, archive, or catalog photos. The pictographs beneath are composed of photographs gathered from other informational sources and are intended to function as texts. Each piece relies on the symbolic juxtaposition of these collaged images for its 'reading.'

My series Unsighted 1992-93 grew out of my friendship with a blind individual and our ensuing conversations about photography and sight, and the disproportionate authority that a photographer exercises over the subject and the viewer. For this project, I spent a year photographing people who were legally blind. I presented their portraits in a square gallery space. When my viewers entered the room, they were surrounded by and confronted with large-scale, uncomfortably close portraits of people whose eyes stare directly at them. The oversized features of the faces were rendered in a sharp and even light, so all surface details appeared clear and precise. There was no information supplied, other than the title of the series and a wall text written in Braille, thus placing sighted people at a disadvantage.

Although the intentions for each of my extended projects may differ, they all begin with just making images. For me, photographs beget photographs, and from this process, I slowly discover what I need to do. There are no rules, but ultimately a new project reveals itself. It’s then that I do the research. Over the course of the past 40 years, I’ve completed six distinct projects. All can be viewed at maryfrey.com.

Hartford Art School

You’ve been lecturing on photography at the Hartford Art School in both the undergraduate and graduate programs until 2017. Looking from this angle on photography as the process of creation you can affect and shape, what was the most memorable project or discussion you led?

One of my most memorable teaching experiences occurred during a critique session in our graduate program about ten years ago. A student was presenting his personal work to the entire class for the first time. Prior to entering our MFA program, he had had a very successful career as an editorial photographer, living abroad for many years. He appeared extremely confident and spoke with authority when he talked about his commercial work. However, in the midst of the critique session, he broke down weeping. It happened, he said, because this was the first time anyone had actually looked at and responded to his personal photography, and how much he appreciated this. At that moment, I realized how significant my role was as a teacher, and how important it was to be honest and clear when critiquing student work.

‘Today, with social media, we are confronted with a barrage of mundane images - selfies of situations that were obviously staged for us, but now go unquestioned. As viewers, we all agree 'to suspend our disbelief' and have faith in the 'truth' of what we see, despite the fact that we know it’s contrived.’

Documentary Photographs

Real Life Dramas (1984-87), perhaps one of the most talked projects you created, shot on a medium format, showcases staged images, which appear as documentary photography. In what way do you think the observer’s gaze is different when looking at the image knowing it’s staged compared to a documented one? What might be the difference in questions and interpretations that arise?

Back in the mid-eighties, the notion that a photograph presents an objective depiction of reality was being questioned by many photographers, including myself. How is meaning attached to an image? How does framing, point of view, rendering, and all the other choices a photographer makes influence this meaning? Can a photograph really capture truth? I would argue that a photograph holds its own truth - or fiction - and therein lies its strength. The fact that we trust what the photograph shows us feeds into this concept, giving it credibility. Thirty years ago, this idea may have been provocative, or at least conceptually thought-provoking. However, today, with social media, we are confronted with a barrage of mundane images - selfies of situations that were obviously staged for us, but now go unquestioned. As viewers, we all agree 'to suspend our disbelief' and have faith in the 'truth' of what we see, despite the fact that we know it’s contrived. My two bodies of work, Real Life Dramas and Domestic Rituals, attempted to do just this.

‘Many questions arose as I grappled with how to create a narrative from these images that would speak to this moment while being true to the past. Where does the meaning of a photograph reside when its intentions have long faded from memory?’

Reading Ramond Carver, 2017

Reading Raymond Carver’s short stories can be disturbing, meeting the raw realism and experiencing the surprise twists of the plot. Which Carver’s story made an impression on you?

I was a Raymond Carver junkie in the eighties, and while I was working on my Domestic Rituals series (1979-83), his stories had a strong influence on me. I can’t really choose just one story or poem that affected me, but I was drawn to his unremarkable characters who go about their daily lives, and then a small event or exchange of words or even a glance may change their situation - or not. His stories are tinged with both sadness and humor and often are open-ended, offering no solutions or conclusions for the reader. In short, they allow us to bring our own experiences to bear when considering the conditions faced by his subjects. I feel my photographs operate in a similar way. They depict middle-class people engaged in everyday routines. Their rooms are described with flat, democratic lighting, so every detail in the scene possesses an equal visual weight and is described with dispassionate accuracy. Actions in my scenes often revolve around a fleeting or mundane moment, frozen in time by the camera. When they are successful, my photographs suggest more than what they show.

Why did you decide to allude to Raymond Carver?

Thirty-five years later, I returned to this body of work in order to produce a book. Many questions arose as I grappled with how to create a narrative from these images that would speak to this moment while being true to the past. Where does the meaning of a photograph reside when its intentions have long faded from memory? I relied on sequencing and a few quotes by Carver to pull it all together, so the title was an easy choice for me - Reading Raymond Carver.

‘I must admit I find it, at times, very liberating to respond to the world unfettered and at other times, frustrating, trying to figure out just where I should point my camera.’

Family, Friends & Strangers

In the ongoing series, you’re working on since 2002, Family, Friends & Strangers, you present moments, which unfold into stories in the viewer's imagination. Each moment is more than it seems: it is a whole life with the cause and effect relationship happening outside of the frame. What did you learn while working on the images and looking back at the moments you captured?

After working on so many distinct projects, I felt the need to just make photographs without the constraints of a philosophy or artist statement to define my parameters. So this latest category (I can’t really call it a series) - Family, Friends & Strangers - is a placeholder for all that work. I must admit I find it, at times, very liberating to respond to the world unfettered and at other times, frustrating, trying to figure out just where I should point my camera. Back in my earlier years, I forced the world to look the way I wanted it or imagined it to be. Now it’s different. I’m slowly abandoning these notions and re-discovering what photographs contain, and opening up myself to all their possibilities. Granted, I’m still the narrator of the story, but I’m learning that the world is a much more interesting place than anything I have to say about it.

‘Since the pandemic, I’ve felt an urge to slow down and take stock in what I’m photographing and how it all fits into a world seemingly flooded with images. To this end, I’ve started working with a large-format view camera, returning to a similar practice I began 40 years ago.’

Upcoming Projects

What are you working on right now?

As I previously mentioned, in 2017 I delved into my archive of images in order to create a book from my earliest Black & White photographs. I titled it Reading Raymond Carver. A year later I tackled the work in my series Real Life Dramas, which originally paired color images with text. To make that book, I abandoned the strict coupling of words with pictures to create its own narrative that still felt true to the original intentions of the work. In thinking about these two books, I realized that the first one asked questions about what choices we make while living our lives, while the second one embraces and celebrates those choices.

I’m currently working on a third book of photographs, which will include work spanning 40 years, acting as a bookend to complete this trilogy. It is inspired by my photograph, My Mother, My Son, and will consider where we have been and what we know while contemplating what is indeed beyond our vision. It is scheduled for publication this year.

Since the pandemic, I’ve felt an urge to slow down and take stock in what I’m photographing and how it all fits into a world seemingly flooded with images. To this end, I’ve started working with a large-format view camera, returning to a similar practice I began 40 years ago. I’m rediscovering the joys of how my lens still organizes space, describes details, and draws the subject on the film. And when I photograph people, I meet them face to face - not hidden behind a camera - when I make my exposures. The process, for me, is performative, and I now produce far fewer photographs than before. I’m really not sure where it will all lead, but I’m willing to follow it along.