The Conversation Beyond The Obvious

Featuring Cole Barash Words by Nastasia Khmelnitski

Website Instagram

The ongoing investigation and observance of human interaction with nature are at the core of Cole Barash’s practice. The research is about the human form and identity and the way it relates to or is affected by the natural element. This interaction can be of a positive and a negative quality, that of nourishing or destroying nature. Cole explains, “I am genuinely curious about the human relationship to the natural world: land, water, air, weather, and all types of environments. How and where we exist within it. When and why do we choose to separate from it and interfere, often destroying it.”

With his work Grimséy (2015), Cole examines people from the fishing community on a small island, while in Smokejumpers (2017), he studies the work of wildland firefighters. In Stiya (2019), Cole presents the intimate story of the birth of his first child interconnected with the Nor’Easter storm. And Sound of Dawn (2020) invites us to learn about the human connection to the color of the Rio Tinto river in Spain caused by the acids from the mines in the area.

Cole Barash is a visual artist located in New York. Cole’s practice is focused on working with digital, analog, and archival photography. He had held numerous solo and group exhibitions in The States, Canada, Europe, and Japan. His last photo book, Sound of Dawn (2020), was published by Libraryman. The previous photo book, Stiya (2019), published by Deadbeat Club Press, became a solo exhibition presented in Tokyo, Japan. In this interview, I speak with Cole about his decision to enter the field of photography stemming from his family’s influence. We discuss the way traveling affects his work and the point of view that Cole is offering through the images. Cole speaks about his interest in nature and the human connection to nature. We examine his passion for raising questions and discovering this relationship through photography. We close the conversation by deep-diving into discussing Cole’s experience working on his two recent books, Sound of Dawn and Stiya.

‘I think that curiosity has stuck with me literally since that first day. The curiosity to experiment, explore, and have an internal conversation.’

My Story

Hi Cole, it’s lovely to meet you! Let’s start with your decision to take the path of a photographer. How did it come about, and what fascinated you in this sphere?

I think I had always been a bit interested in art and then photography. My mother is a landscape designer, which I recently realized must have had a large impression on me of how I see lines, shapes, and colors in the world, as her work is beautiful. My father was a hobbyist photographer, as was his father, so I suppose that kind of trickled down. My grandfather built a darkroom in his house and printed quite regularly. I remember being very young, like 6 or 7, and being down there with him. When he passed, I was able to take an object with me, and I chose the glow-in-the-dark tape from the darkroom, haha.

I believe when I was 11 or 12, I started bringing my father's Canon AE-1 out into the world and became obsessive quite quickly. Something about spending time with an object when you are making decisions in terms of feeling and making compositions and then see it transformed into a negative or prints was fascinating to me. I think that curiosity has stuck with me literally since that first day. The curiosity to experiment, explore, and have an internal conversation.

‘True magic, the true beauty, is right in your backyard. The secret is to explore every square inch of where you live. I really took this to heart as then I started shifting my practice, research, and work to include this.’

Travel

Travel is the central part of your experience that influences your work, books, and exhibitions. Which place had a major influence on you on a personal or professional level?

I am going to answer this in a two-part answer. Yes, travel and experiencing other places, cultures, and types of lives have been an essential part of my practice. However, recently a friend and amazing artist, Jim Mangan, maybe a few years ago, told me about a famous writer (blanking on the name) who, in his writing, had included a statement about how so many people are obsessed with traveling around the world and exploring endlessly. Whereas, true magic, the true beauty, is right in your backyard. The secret is to explore every square inch of where you live. I really took this to heart as then I started shifting my practice, research, and work to include this. It's definitely been super refreshing. Anyways, yes, the world is a big and beautiful, complicated place.

What are some of the destinations you still want to visit?

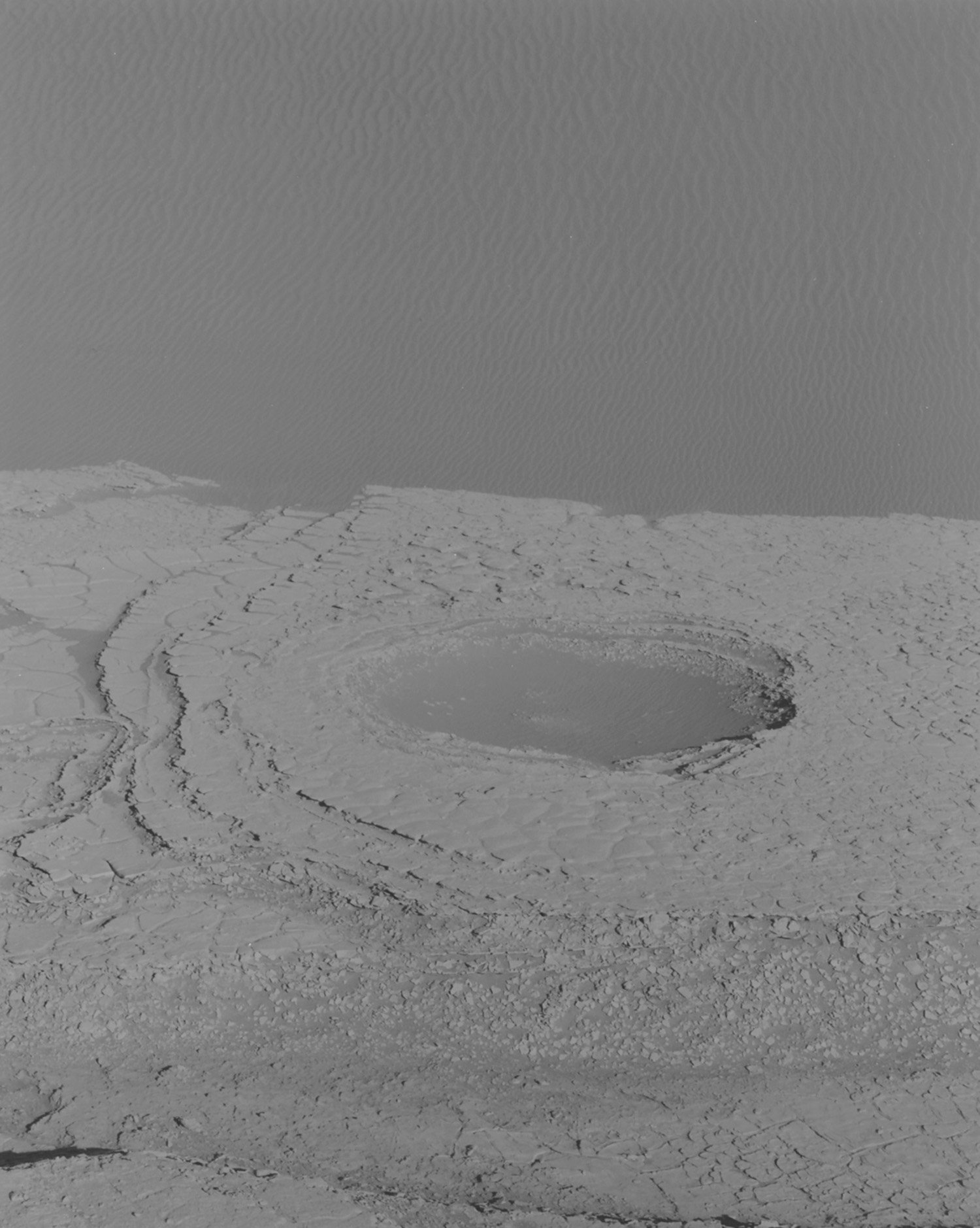

To answer the question in a location-based answer, I would say I am continually drawn back to the desert. Only recently though, the past few years. I think it's being a foreigner to that type of land, being from the northeast. The desert is so new and unknown to me, especially to make work. Besides that, on a personal level, I quite enjoy surfing in Indonesia, Chile, and Mexico. Whenever possible, to get to any of these places, I really try to.

‘I am genuinely curious about the human relationship to the natural world: land and water. How and where we exist within it. When and why do we choose to separate from it and interfere, often destroying it. I am interested in reading and deeply looking for the conversation similarities and differences beyond the obvious.’

Topics

Some of the recent themes your work focuses on are back pain for a project BACKS, snowboarding for the film Neighborhood, and you continue to explore topics for The Western Slope project. Your approach includes a sincere interest in the human, their experiences, and the deep connection to nature or each other. Which questions are you working to answer with your work today, and how does it differ from what you were doing several years ago?

Great question. In the past few years, I have arrived and discovered that nature has and will continue to be a very large part of my practice. My upbringing, being heavily spent in outdoor situations with my parents, sometimes in the deep wilderness, in harsh environments of weather, or the middle of the vicious ocean alone — has definitely left an impression on me. I am genuinely curious about the human relationship to the natural world: land and water. How and where we exist within it. When and why do we choose to separate from it and interfere, often destroying it. I am interested in reading and deeply looking for the conversation similarities and differences beyond the obvious. As well as just understanding how things in that world (nature) operate, flow, exist and survive, seeing how that reflects into my own.

It may be something I spend my entire career, the next 50 years, contributing to and making work about, yet still, not knowing anything further; however, it is a space that I feel excited about, and I have a personal connection to, which, therefore, I know is right to keep going and pushing hard, day in and day out.

Some bodies of work may be geared more toward the human relationship to land, such as The Western Slope (2016-ongoing) or Grimsey (2015). Then other works may be more abstract and not so literal that are more energy, feeling, and emotional-based, such as Sound of Dawn (2020) and Stiya (2017). I think what personally keeps me interested is that there is room to explore and experiment without such rigid boundaries. When at the end of the day, all the work(s) should be able to live together as one conversation and output. I mean, look at Richter — looking at his work throughout his career, how wildly it flowed through different mediums and ideas, yet it still reads so well. It astonishes me every time I revisit it, almost like a light that shows that it is possible to exist and continue in that unconventional approach. I highly value it.

In regards to how the work has differed since several years ago, I think it has really just expanded and continued to develop and be refined. I look back at some very early work and am embarrassed at how bad it is. Yet I understand that it is part of the process of making work — you fail. You fail terribly. Then hopefully, learn from it (if at the time you have someone to point things out) and continue to move on in a humble way. It still has a very long way to go until I consider anything good or substantial has been made.

‘It was when during our breaks they just naturally hung out together, mostly sitting and lying, is when I saw the beautiful symmetry of how things landed or were presented. A true example of the organic process, I suppose.’

Sound of Dawn

The recent book Sound of Dawn (2020), published by Libraryman, is a search for the connecting dot between the landscape and the human at a certain point in space and time. Traveling through Portugal and Spain, observing and ‘collecting’ shapes found in nature, the book presents an experience of colors, landscapes, and the way a person immerses into nature. When comparing images from the final selection that made it to the print and those that did not, what stands out for you? What was important in shaping the visual story in the book?

I began this work during a residency in Portugal, and it took two years to make. One evening, I was sketching some of the landscapes of the photographs I had made digitally that week, and I started to see this familiar form of lines and shapes of the human body. This eventually led me into the studio, where I had set up several human bodies lying together naked. I looked at a close level of where and how they existed together. At first, I had specific ideas of how I posed them together, etc., yet it was when during our breaks they just naturally hung out together, mostly sitting and lying, is when I saw the beautiful symmetry of how things landed or were presented. A true example of the organic process, I suppose.

After doing a few of these sessions, I brought the prints together with the nature-based images to begin navigating the dialogue. Then, eventually, when I had a good flow, I handed everything over (which I never usually do) to Tony Cederteg at Libraryman, who would be publishing the work. At this point, it became a collaboration as he then took the work and made his sequence of the work, drawing and finding his energy through the edit. We went back and forth on a few revisions before the final edit was agreed on. At the time, during the shutdown, I was reading a lot of text from different artists, dead and alive. This one quote had really stuck with me, from Robert Adams, which also felt very connected to the work at the time, so Tony decided to open the book with that quote, which I was so psyched on.

‘There is a project of the mirror and the midwife during the birth, and it's just odd. I think, in the mirror, it just reflects the wall or something, but the midwife has this expression, almost a gaze, that is just almost blank.’

Stiya

The book Stiya (2019), published by Deadbeat Club Press, presented in a solo exhibition in Tokyo, is a personal work. The story includes images of your first child and the storm taking place at the time. The physical and the metaphorical worlds unite into an experience that is personal and universal in a way. Looking back at the process of making Stiya, what are the emotions that surface? What do you think is the main image that defines the book and this experience for you?

A friend once told me that going out into the world and making work has gotten him through some of the hardest times of his life. More so, the exercise of outputting almost. That always stuck with me. Having a child is scary. A lot can go wrong very quickly. You also walk into a place as two and come out as three — also very crazy to think about. In addition to all of this, your life dramatically changes in that instant, forever.

Leading up to this and during it was a quite stressful time for me. I was really nervous, had anxiety, and had these wild emotional rollercoasters of highs and lows. A day or two before the birth, we had this huge storm hit where we were living at the time. A large winter blizzard called a Nor’Easter where winds of up to 90 mph blew, snow spit sideways, and the world had shut down. I decided to go out into it, output, think, and even more so, react and create. These were the photographs I made of the storm.

Then during the birth, I really did the same. I was making compositions of everything that was happening, thoughts that I had, and weird things I observed — energy, objects, lines, shapes, and the environment in the room. In the following few months, I started to make prints of the work in my studio. This was when, for the first time, I started to see the connection of energy in two very different but pure forms.

As for an image that represents that work to me, at least I would say… There is a project of the mirror and the midwife during the birth, and it's just odd. I think, in the mirror, it just reflects the wall or something, but the midwife has this expression, almost a gaze, that is just almost blank. It's so hard for me to describe, but I think it has this odd quality that I quite enjoy.

A Sneak Peek

Could you provide us a sneak peek into the project you’re currently working on or some of the themes in development?

For the past two years, I have been working on a series, When the Wind Blows North. It's a collaborative set of images with my father I've been making with him since he passed away in early 2020. I now feel I am with him the most when I am completely solo, out in the wilderness, sometimes for several days at a time.

So I have been viewing these short expeditions I have been doing solo with him. The photographs that we have made together out there have also become material for some sculptures, which will also be part of the work. I am hoping this will be released sometime at the end of next year.