It’s a kind of fantasy: on death, extinction and climate crisis

Ana Zibelnik' work focuses on creating an atmosphere of perpetuity through depicting the themes of elapsing time, mortality and inevitability of death. The viewer learns to zoom in and out, moving from the perspective of the individual human driven driven by their own desires and acting according to their will towards the perspective of humankind, a living organism that is leading towards its own destruction, while still having the power to have a shift the course of events. The second layer of exploration is the broader state of the natural environment, contemplating what will persist and survive leaving a trace beyond human existence.

In this interview, we speak with Ana about her decision to leave Ljubljana and move to The Netherlands to build and advance her career in the local and global scenes. We discuss the project We are the Ones Turning and the exploration of the distinction between the experience of personal mortality and the extinction of humankind. Ana speaks about one of the symbolic images of the project in which turning hands are portrayed. She describes the mechanism behind the motorized flipbook she created for the exhibition with the images of turning hands and the connection to the sense of time, “The mechanism used in the flipbook is actually very similar to a clock, but what I especially loved about it is that the elastic that turned the images was bound by hand, therefore resulting in slight variations in rhythm and speed, kind of like the experience of time.” Ana shares details about her collaborative project Fault Line with Jakob Ganslmeier, which aims to bridge gaps between different activist groups and generations to allow each to contribute to and address the cause of the climate crisis.

Ana Zibelnik, a Slovenian artist and photographer based in Hague, the Netherlands, holds a BA in Visual Communication Design from the University of Ljubljana and an MA in Film and Photographic Studies from Leiden University. Since 2020, Ana has been working as a duo with Jakob Ganslmeier on projects such as Fault Line, which received 1st prize at the Kranj Foto Festival in Slovenia. The duo works to address the topics of climate change and the effect of social issues on the young generation. Their video work Bereitschaft is currently on display at the GIGA exhibition at Foam Photography Museum Amsterdam until June 9th.

Words by Nastasia Khmelnitski

‘So when I say the Dutch scene has been nice to me, I do mean it, but as a foreigner, you also work twice as hard to get the same recognition and access to these opportunities as somebody born here.’

My Narrative

Hi Ana, it’s a pleasure to meet and have this opportunity to discuss your work with you! Originally, you’re from Ljubljana, Slovenia, where you gained your BA degree in Visual Communication Design from the University of Ljubljana. Currently, you’re located in the Netherlands, where you completed your MA in Film and Photographic Studies at Leiden University. What are the opportunities available in the field of photography in the Netherlands, and how does it differ from Slovenia?

Hi, thank you for having me. It’s lovely to be in the company of other photographers published on WÜL — I discovered some great projects via the platform lately.

It’s hard to answer this without making it seem like things are all great in the Netherlands and bad in Slovenia, but the Dutch cultural scene has been pretty good to me. To be fair, I haven’t stayed in Slovenia long enough to really try and build a career. I can only say that the feeling I left with was a little bit bitter and that I never managed to prove that what I wanted to do was an actual job with responsibilities and not a hobby. While living abroad, I’ve often had the wish for more exchange and also actively tried to engage Slovenian artists in projects I have been part of here. There are people I can rely on and know that I will maintain these relationships in the long term, for example, the framing studio and certain designers I work with. Still, I also sense that fellow photographers or acquaintances sometimes assume it’s been easier for me and others who moved away because of there being more opportunities. Things are never that simple — if I had stayed, I would have had friends, people who follow and support you from the very first steps of your career, and a professional network. I know how comfortable living in Ljubljana feels, although it can be financially more challenging to sustain your practice. When you move away, you kind of have to accept that you will lose every bit of that comfort. So when I say the Dutch scene has been nice to me, I do mean it, but as a foreigner, you also work twice as hard to get the same recognition and access to these opportunities as somebody born here. You have to prove your commitment, which is understandable.

Returning to the situation in Slovenia, I have been working with a Ljubljana-based gallery, Galerija Fotografija, for the past years, and I’ve really grown to appreciate how much they invest toward bringing more visibility to local artists, especially young and less established ones. Recently, Fault Line (a series I will return to later) also won the first prize at Kranj Foto Fest, which is a new international photography festival established in 2021. Getting these little bits of recognition at home has meant a lot to me because my relationship with Ljubljana is a little troubled, but this is mainly so because of personal disappointments. I don’t want to generalise or make an unfair comparison between a rich, privileged country and one that is still developing.

To give some concrete examples of the opportunities I mentioned earlier, one of the first things that I noticed after moving to the Netherlands was the level of professionalism that follows when a medium is taken seriously. Immediately after my studies, I started working for the Dutch photography producer Paradox (Bas Vroege). I remember being so fascinated by the idea that there even is such a role (producers) in the field of photography. The second thing was realising that people respected what I did without looking down on me for being an artist and wanted to engage with the work. It is so simple, really, but the feeling was completely new to me. Unfortunately, things are changing in the Netherlands too, and photography faces challenges in maintaining its place in the arts. Still, it is generally possible for young artists to at least give their careers a try, even if they don’t have rich parents. There are so many funds and talent programmes which are dedicated to helping recent graduates kickstart their practice. It hasn’t been easy, and I certainly work a lot, but I manage to make a living with photography, which I never thought of being possible back at home.

‘I always felt like the idea of the world ending at a certain point is more comforting to humans and easier to accept than the individual experience of death.’

We are the Ones Turning

The series, We are the Ones Turning, works with a theme of mortality and time, connecting the viewer to the current state of ecology and the dangers of extinction humankind faces. What I find fascinating is the atmosphere and the actual sense of time and death created through the powerful juxtaposition of the young girl and the older couple, the rope hanging on the building, and the hands showing in American Sign Language the gesture for ‘death.’ The viewer is reminded of the biological clock ticking and the time that escapes. How important is it to filter the concepts through your personal understanding of time and death, your life experiences, and your relation to the time we have left (that might also have a connection to the beliefs stemming from family and growing up)?

In We Are the Ones Turning, I decidedly focused on the human experience of death — the very private and individual one. Extinction as a sort of collective, mass-scale death evokes a different kind of fear than the thought of only yourself leaving while the world as you know it continues. I always felt like the idea of the world ending at a certain point is more comforting to humans and easier to accept than the individual experience of death. It’s a kind of fantasy, of course, because extinction is very slow, at least when compared to a human lifespan. So the thought of us being the only mortals, the only ones aware of our mortality, is really what guided the creation of the series and is most clearly manifested in the gesture of the turning hands that you mention. I actually ended up turning the images of the hands into a motorised flipbook and making it part of the exhibition installations. The sound of the cheap motor, not perfectly rhythmical yet always running in circles, gave the series a nice atmospheric background. The mechanism used in the flipbook is actually very similar to a clock, but what I especially loved about it is that the elastic that turned the images was bound by hand, therefore resulting in slight variations in rhythm and speed, kind of like the experience of time.

In terms of filtering this work and the images through my own experiences, I was always reserved in saying this work is about me. It’s not about me although I do have a strong fascination with this topic since I can remember, and I used personal memories as a base for staging the images. I realised that after all, you can only make something universal if you create from your own experience and understanding rather than trying to generalise. I certainly acquired the visual vocabulary from Slovenian and the wider Slavic cultural space, which can be a little heavy in how it deals with death. There is a rather large gap, I feel, between how strongly death and grief are experienced and how little they are talked about. By saying 'strongly,' I don’t mean to diminish any other cultural experience — it’s always all-consuming and always difficult, but in certain philosophies, there is also a lightness to it, and I never felt any lightness in how my family dealt with it.

‘When we learn that a certain thing is about to disappear, we first try to document and file it properly.’

Immortality is Commonplace

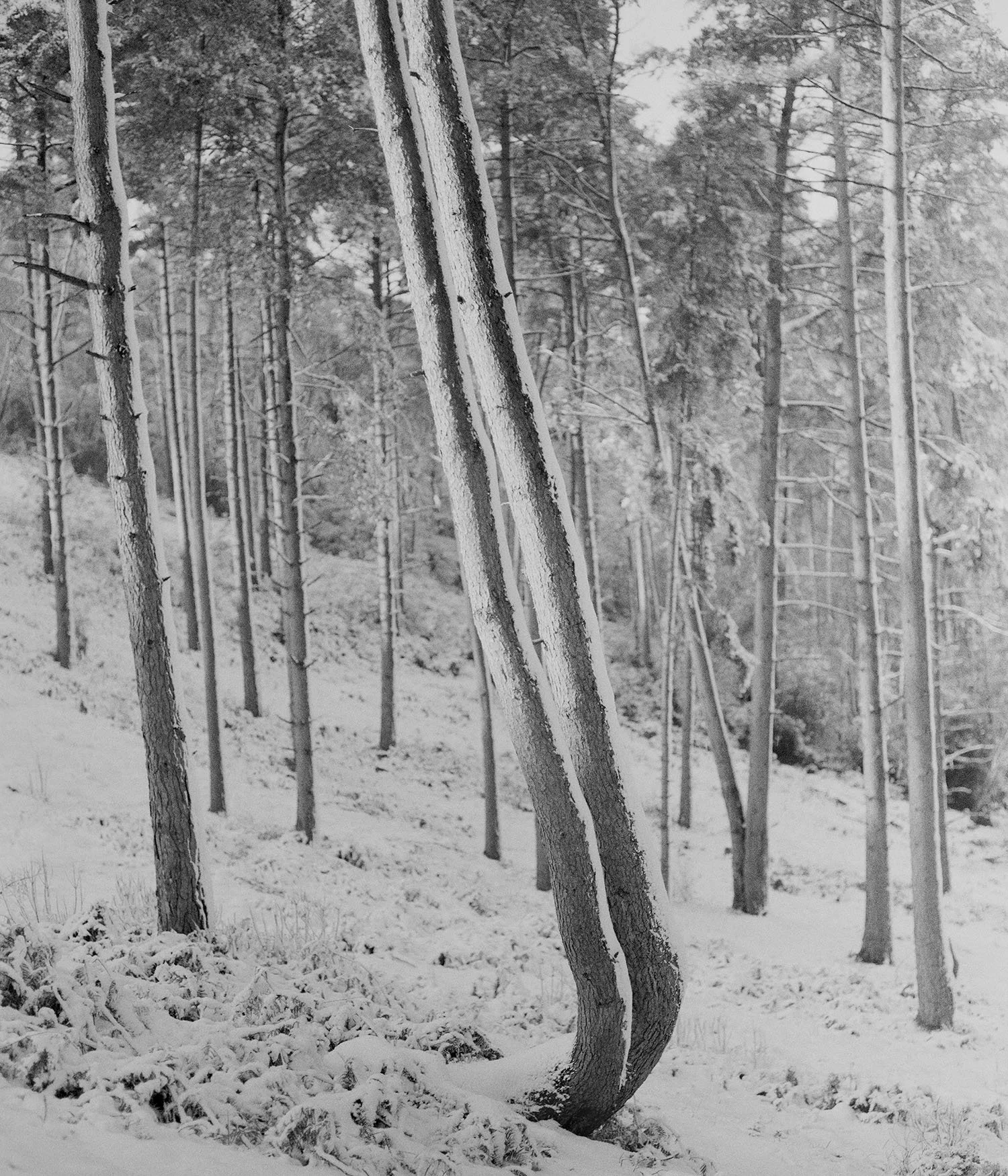

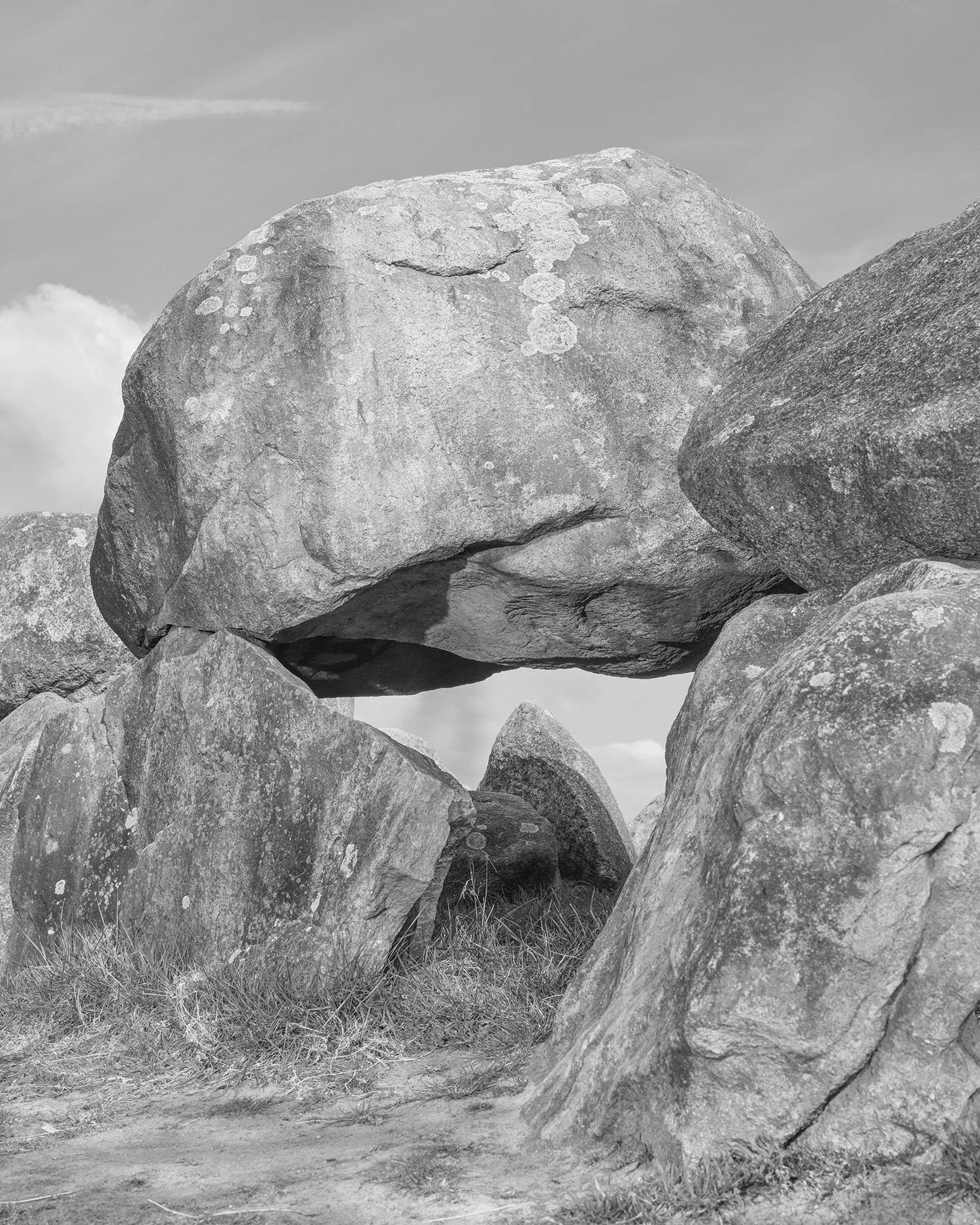

In Immortality is Commonplace, you explore climate change, contrasting it to the experience of human beings as opposed to one of the durable organisms. The perception of time, development, and death are incomparable between humans, for whom life is an absolute leading to death, and durable organisms which persevere and last in a very different pace of time. What was the process of research and the theory behind the series? How did it help in the selection of the images to create this narrative?

Immortality is Commonplace started from thinking about the changing role of photography in times of the climate crisis. I was finishing my MA at Leiden University at the time, so I had the classics of photography theory always at the back of my mind. And again, these classics all linked photography to death. I thought a lot about the human impulse to preserve things — to ‘save them from the corruption of time’ (I think Bazin said that), which is not different when we look at how we approach species under the threat of extinction, even those whose temporalities are naturally much larger than our own. When we learn that a certain thing is about to disappear, we first try to document and file it properly.

I was really fascinated by lichens and other ‘biologically immortal’ (extremely durable) organisms because they are not exempt from this threat of extinction or the effects of the climate crisis. But under perfect conditions, they could far outlive humans. They even have this fascinating capacity to store information about the composition of air for years back, so in a way, they are also a medium. I was asking myself — who is recording whom? And so, in the photos, I tried to visualise the tension of who is going to live longer — the referent (in this case, lichens) or the photograph. While making this work, I really enjoyed reading Joanna Zylinska and her idea of photography as a life-making practice. It’s now been years since I read Nonhuman Photography, but I think she describes photographs as little slices of time, downsizing it so we can grasp it as humans.

‘We appreciate the more humanitarian approaches to solving the climate crisis. It’s really a core message of our work, emphasising that we are all in this together.’

Fault Line

Fault Line is a project you’re working on with Jakob Ganslmeier that was shown in Rotterdam as part of the Prospects 2024 exhibition. You address the issue of the climate crisis through the experience of traveling throughout Italy and encountering climate activists. What have you learned from those conversations and interviews? And what is it like for you to work in a duo with Jakob on this project?

Indeed, we focused on activism and even more specifically, climate anxiety being one of the main reasons driving people into activism during our work in Italy. It’s such an important part of growing up nowadays. In Italy, the climate movement is fairly strong, with a lot of local groups and organisations acting on behalf of the bigger movements. What has been the most striking is how understanding the young activists were toward the wider implications of taking radical climate action. Of course, considering the rapidly worsening conditions, radical changes are necessary, and they should happen sooner rather than later, but in wealthier European countries, people often end up moralising each other’s actions, pointing fingers at who’s a good activist and a good neighbour, shopping at the right eco-friendly supermarket and driving an electric car, and so on. But very often, your socio-economic conditions don’t leave you much choice. In Italy, 15-year-olds were telling us that they desperately want to reduce car traffic in their city, but they don’t feel comfortable blocking the road because they know that somebody could lose their job because of it.

Every climate movement has a different approach in this sense: some are more media-forward, looking to bring attention to the cause by creating striking images, and some are in for the slower battles, addressing the European Parliament or writing letters to the small town mayors. We see the importance of these different approaches — how they supplement each other, but personally, I believe I can speak for Jakob as well, we appreciate the more humanitarian approaches to solving the climate crisis. It’s really a core message of our work, emphasising that we are all in this together, and deepening the divides between younger and older generations is not helping.

We had a similar experience in Greece. When the wildfires started last summer in the Alexandroupoli area, we came across a couple of media reports suggesting it was the migrants setting the fires, and we immediately felt drawn to look into the emerging narrative. The region is well known as a migrant route from Turkey to Greece. When you read this from your sofa in the Netherlands, you honestly think how idiotic such an assumption is, and it makes you angry. But when you spend a week with a Greek family in some small village, left alone by the government and with little access to information, you have to let go of your judgment.

According to what many people told us during our interviews, the Greek government blamed climate change as a reason for the fires, not because they genuinely believed so, but simply because it lifted the financial responsibility. A little bit in the sense of "It’s a higher power, so there is nothing we could have done to prevent it." Understandably, if this is what you’re told after your house burns down, you are not too inclined to agree. You need a reason, somebody to blame, and most importantly, a plan on how to go on with your life after having lost everything. If your government is not there for you, providing some sort of guidance in times of crisis, the easiest narratives tend to stick. In general, returning to the goals of our project, our idea is never to say hey, look at these people and their horrible conspiracies, but approach it with empathy. If you really try to understand where somebody's ideological standing is coming from, you’ll have a much higher chance of opening a discussion than when you are starting from judgment.

Working as a duo has made the work so much stronger. From the outside, it might seem very romantic — travelling to Italy, Greece, or Spain and being on the road together. We certainly enjoy being out and producing new work a lot, but it takes a tremendous amount of motivation to actually go and do it. Very often, the conditions are less than ideal. In Italy, when we worked in the dried-out fields in the middle of the historic heat waves last July, I completely collapsed from the heat. And somebody still had to drive us to the apartment, charge the batteries, and empty the cards so we could wake up early the next morning and do it again. Also, with this project, we took a significant financial risk, starting the production before we had any proof of funding — because Italy was flooded in May and not in July (by then, it was all dried out and looked like a desert), and we only got the results in July. Since we started working together, it often happened that we moved super fast in the planning of our projects, perhaps that has something to do with the nature of the topic. It has been a rollercoaster psychologically, and I can’t imagine powering through all of that on my own.

Upcoming Projects

What theme or narrative are you researching, and what can we expect from you in the upcoming months?

Jakob and I just produced a new video work, which premiered at our exhibition GIGA at Foam Photography Museum Amsterdam (open until June 9, 2024). Bereitschaft, as it is called, delves into the glorification of the 'sculpted' male physique and the advocacy of self-discipline within TikTok fitness trends, examining how these inclinations mirror fascist tendencies and serve as symptoms of a right-wing ideological shift. The work is a continuation of a longer research on the way social media aids the radicalisation of youth.

In this exhibition, we also presented Gigapedia, a huge glossary, featuring different hate symbols, meme characters, and public personalities we encountered during our research. Lately, we have been doing a lot of workshops on visual literacy using this same visual material, trying to understand where humorous online content such as memes turns into something highly ideological, potentially luring a young person down the rabbit hole of becoming radicalised.

Regarding where this might take us in the future, it is perhaps a little early to say anything with certainty. But besides continuing Fault Line over the warmer months, we are interested in exploring the idea of what is modern-day spirituality. Or, to be precise, what is spirituality when it is mediated through TikTok? The collective tendency toward ‘healing’ is a kind of antidote to the fitness trends and the imperative to ‘toughen up,’ but in a way, it also feels like a response to the same symptom as getting yourself into perfect physical shape — the ‘readiness’ that Bereitschaft talks about. The common denominator seems to be that the world is sick, and we are trying to cure ourselves by following TikTok trends.